The Strategic Imperative of Network Configuration: Design, Management, and Automation

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

Abstract

Network configuration stands as the foundational pillar of an organization’s digital ecosystem, meticulously orchestrating seamless communication and data interchange across a diverse array of devices and interconnected systems. This exhaustive research report undertakes an in-depth exploration into the intrinsic elements of network configurations, meticulously dissecting the multifaceted roles and operational components of fundamental networking devices such as routers, switches, and firewalls. It meticulously examines established best practices and emerging methodologies for architecting and deploying configurations that not only elevate network performance to optimal levels but also fortify its security posture against evolving threats. The report systematically identifies and analyzes common vulnerabilities and operational pitfalls that frequently precipitate misconfigurations, subsequently elucidating advanced techniques and strategic frameworks for proactively managing and mitigating configuration drift. Furthermore, it comprehensively investigates the transformative influence of network automation across the entire configuration lifecycle, offering a holistic and profoundly detailed understanding of this critical domain in contemporary information technology infrastructure. By integrating theoretical foundations with practical applications, this study aims to provide a robust resource for professionals and researchers alike, highlighting the strategic importance of well-managed network configurations in maintaining operational resilience and competitive advantage.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

In the relentless dynamism of the digital age, the foundational efficiency, unwavering security, and inherent resilience of an organization’s network infrastructure are not merely advantageous but absolutely paramount. Network configurations, encompassing the systematic setup, meticulous customization, and ongoing management of critical hardware and software components such as routers, switches, firewalls, and other specialized networking devices, are unequivocally central to ensuring optimal operational performance, safeguarding invaluable data assets, and maintaining continuous business operations in the face of ever-present threats. The implications of misconfigurations are far-reaching and severe, potentially culminating in critical security vulnerabilities that expose sensitive data, precipitous performance degradation leading to service interruptions, and significant operational disruptions that can cripple organizational productivity and reputation.

Therefore, a profound and thorough understanding of the granular components that constitute network configuration, coupled with an adherence to rigorously defined best practices and sophisticated management strategies, is not merely beneficial but unequivocally essential for architecting, deploying, and maintaining a robust, secure, and highly available network infrastructure. This report moves beyond a superficial overview, delving into the intricacies of each component, the rationale behind specific configuration choices, the evolving landscape of threat vectors that necessitate sophisticated security measures, and the revolutionary impact of automation in transforming traditional network management paradigms. It underscores the transition from reactive problem-solving to proactive, intelligent network governance, positioning network configuration as a strategic asset integral to achieving organizational objectives in an increasingly interconnected and complex digital world.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Components of Network Configuration

Network infrastructure is fundamentally comprised of various interconnected devices, each with a distinct role in facilitating data flow, ensuring security, and optimizing performance. The proper configuration of these components is critical to the network’s overall health and efficiency. We will delve into the primary devices: routers, switches, and firewalls, along with other essential elements.

2.1 Routers

Routers are sophisticated networking devices primarily responsible for forwarding data packets between distinct computer networks. Operating at the network layer (Layer 3) of the OSI model, they utilize complex routing tables and a myriad of routing protocols to determine the most optimal and efficient path for data transmission, thereby ensuring accurate and timely delivery across heterogeneous networks. The intelligence of a router lies in its ability to examine the destination IP address of incoming packets, consult its routing table, and then forward the packet out the appropriate interface towards its ultimate destination.

2.1.1 Routing Protocols

Routing protocols are the algorithms and rules routers use to exchange routing information, build routing tables, and select optimal paths. They are broadly categorized into Interior Gateway Protocols (IGPs) and Exterior Gateway Protocols (EGPs).

-

Interior Gateway Protocols (IGPs): These protocols operate within a single Autonomous System (AS), which is a collection of IP networks and routers under the control of one or more network operators that presents a common, clearly defined routing policy to the Internet. Key IGPs include:

- Routing Information Protocol (RIP): An older distance-vector protocol that uses hop count as its metric. It is simple to configure but suffers from slow convergence and a maximum hop count limit, making it unsuitable for large, modern networks.

- Open Shortest Path First (OSPF): A link-state routing protocol that efficiently determines the shortest path using Dijkstra’s algorithm. OSPF creates a hierarchical structure with areas, which significantly improves scalability and reduces routing update traffic. Proper configuration involves defining areas, interfaces, and authentication methods.

- Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (EIGRP): A Cisco-proprietary hybrid routing protocol that combines features of both distance-vector and link-state protocols. It uses a composite metric based on bandwidth, delay, reliability, and load, offering fast convergence and efficient use of network resources. EIGRP configuration requires defining autonomous system numbers and network statements.

-

Exterior Gateway Protocols (EGPs): These protocols are used to exchange routing information between different Autonomous Systems, typically connecting an organization’s network to the internet or to other organizations. The predominant EGP is:

- Border Gateway Protocol (BGP): BGP is the de facto standard for inter-AS routing on the internet. It is a path-vector protocol that considers various attributes (AS path, next-hop, local preference, MED) to make routing decisions. BGP configuration is highly complex, involving peering relationships with external ASes, route filtering, and policy implementation to control traffic flow.

2.1.2 Advanced Router Functions

Beyond basic packet forwarding, modern routers perform a suite of advanced functions crucial for network security, resource management, and remote access:

- Network Address Translation (NAT): NAT allows multiple devices on a private network to share a single public IP address when accessing the internet. This conserves public IP addresses and adds a layer of security by hiding internal network topology. Types include Static NAT (one-to-one mapping), Dynamic NAT (many-to-many, dynamic mapping), and Port Address Translation (PAT, many-to-one using port numbers).

- Virtual Private Network (VPN) Support: Routers can terminate VPN connections, creating secure, encrypted tunnels over public networks. This enables secure remote access for users or site-to-site connectivity between geographically dispersed offices. Common VPN technologies include IPsec, SSL VPNs, and Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE) tunnels.

- Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) Server: Routers often act as DHCP servers, automatically assigning IP addresses, subnet masks, default gateways, and DNS server information to client devices, simplifying network administration.

- Access Control Lists (ACLs): ACLs are sets of rules used to filter network traffic based on criteria like source/destination IP addresses, port numbers, and protocols. They are fundamental for security, segmenting network access, and controlling traffic flow, operating on both ingress and egress interfaces. ACLs can be standard (source IP only), extended (source/destination IP, ports, protocols), or named for easier management.

- Quality of Service (QoS): Routers implement QoS policies to prioritize critical applications (e.g., VoIP, video conferencing) over less sensitive traffic. This involves mechanisms like classification, marking, queuing, and traffic shaping to ensure performance guarantees.

2.1.3 Router Types

Routers are typically deployed in a hierarchical manner:

- Edge Routers: Connect an organization’s network to external networks (e.g., the Internet Service Provider). They often handle NAT, firewall functions, and VPN termination.

- Core Routers: Form the backbone of a large network, designed for high-speed packet forwarding between various distribution layers. They prioritize performance and redundancy.

- Distribution Routers: Aggregate traffic from access layer switches and provide policy-based connectivity to the core. They often perform inter-VLAN routing, ACLs, and QoS.

Proper configuration of routers is paramount for maintaining network performance, establishing robust security boundaries, and enabling efficient inter-network communication.

2.2 Switches

Switches are fundamental networking devices that connect multiple devices within a Local Area Network (LAN), facilitating communication by forwarding data frames based on MAC addresses. They operate primarily at the data link layer (Layer 2) of the OSI model. Unlike older hubs that broadcast traffic to all ports, switches intelligently learn the MAC addresses of connected devices and forward frames only to the intended destination port, significantly reducing network collisions and improving overall performance.

2.2.1 Switch Operation and MAC Address Learning

When a switch receives a frame, it records the source MAC address and the incoming port in its MAC address table (also known as the Content Addressable Memory or CAM table). If the destination MAC address is already in the CAM table, the switch forwards the frame only out the corresponding port. If the destination MAC address is unknown, the switch floods the frame out all ports (except the incoming port) until the destination device responds, allowing the switch to learn its location.

2.2.2 Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs)

VLANs are a critical feature of managed switches, allowing a single physical switch to be logically segmented into multiple broadcast domains. This provides significant benefits:

- Network Segmentation: VLANs isolate traffic, reducing broadcast domain sizes and thereby minimizing broadcast storm impact and improving network performance.

- Enhanced Security: By separating different departments or types of traffic (e.g., guest Wi-Fi, voice, data) into distinct VLANs, unauthorized access between segments is prevented, limiting the scope of potential security breaches.

- Flexibility and Scalability: Devices in the same VLAN can communicate even if they are on different physical switches, and VLANs simplify network reorganization without physical rewiring.

VLAN Trunking: To allow VLANs to span across multiple switches or to routers for inter-VLAN routing, trunk links are used. These links carry traffic for multiple VLANs, typically using the IEEE 802.1Q standard for tagging frames with their respective VLAN IDs. Configuration involves defining VLANs, assigning ports to VLANs (access ports), and configuring trunk ports.

2.2.3 Spanning Tree Protocol (STP)

Network designs often incorporate redundant links between switches to ensure high availability and fault tolerance. However, these redundant links can create switching loops, leading to broadcast storms, MAC address table instability, and network meltdown. STP (IEEE 802.1D) is a Layer 2 protocol designed to prevent such loops by intelligently blocking redundant paths while still providing a redundant failover path.

- Operation: STP operates by electing a root bridge, then determining the shortest path from all non-root bridges to the root bridge, and finally blocking redundant paths. Ports transition through various states (blocking, listening, learning, forwarding).

- Variants: Rapid Spanning Tree Protocol (RSTP – 802.1w) offers faster convergence than traditional STP. Multiple Spanning Tree Protocol (MSTP – 802.1s) allows multiple STP instances to run, mapping different VLANs to different instances, which is useful in complex networks.

- Configuration: Involves setting priorities for switches to influence root bridge election and configuring port characteristics like PortFast and BPDU Guard to optimize convergence and prevent accidental loops.

2.2.4 Quality of Service (QoS) on Switches

Managed switches can implement QoS policies to prioritize certain types of network traffic. This is crucial for real-time applications like Voice over IP (VoIP) and video conferencing, which are highly sensitive to delay and jitter.

- Mechanisms: QoS on switches typically involves classifying traffic (e.g., by VLAN, MAC address, IP address), marking it (e.g., using 802.1p CoS or DSCP), and then applying queuing mechanisms (e.g., Weighted Fair Queuing, Class-Based Weighted Fair Queuing, Low Latency Queuing) to ensure prioritized traffic receives preferential treatment.

2.2.5 Security Features on Switches

Switches are not just about connectivity; they offer several features to enhance LAN security:

- Port Security: Restricts the number of MAC addresses allowed on a port and can statically assign MAC addresses, preventing unauthorized devices from connecting.

- DHCP Snooping: Prevents rogue DHCP servers from operating on the network and mitigates DHCP starvation attacks.

- Dynamic ARP Inspection (DAI): Protects against ARP spoofing and poisoning attacks by validating ARP packets against DHCP snooping binding tables.

- Storm Control: Prevents broadcast, multicast, or unicast storms from overwhelming the network by limiting the traffic rate on an interface.

2.2.6 Switch Types

Similar to routers, switches are deployed in a hierarchical model:

- Access Layer Switches: Connect end-user devices (computers, printers, IP phones) to the network. They are typically Layer 2 switches and implement features like VLANs, port security, and QoS for end devices.

- Distribution Layer Switches: Aggregate traffic from access layer switches and provide connectivity to the core. They often perform Layer 3 routing (inter-VLAN routing), implement ACLs, and enforce policies.

- Core Layer Switches: Provide high-speed, fault-tolerant backbone connectivity for the entire network. They are typically Layer 3 switches optimized for forwarding performance and redundancy.

Proper configuration of switches is essential for optimizing network performance, effectively segmenting traffic, enhancing security, and ensuring high availability within the LAN environment.

2.3 Firewalls

Firewalls are critical security devices that serve as a primary line of defense, monitoring and controlling incoming and outgoing network traffic based on predetermined security rules. Their fundamental purpose is to establish a robust barrier between trusted internal networks (e.g., an organization’s LAN) and untrusted external networks (e.g., the internet), thereby protecting against unauthorized access, malicious attacks, and data breaches.

2.3.1 Firewall Types and Evolution

Firewalls have evolved significantly from simple packet filters to highly sophisticated security platforms:

- Packet-Filtering Firewalls: The earliest and simplest type, these operate at the network layer (Layer 3) and transport layer (Layer 4) of the OSI model. They inspect individual packets against a set of rules (source/destination IP, port numbers, protocol types) and either permit or deny them. They are stateless, meaning they do not keep track of ongoing connections.

- Stateful Inspection Firewalls: These are the most common type of traditional firewall. They operate at Layer 3 and Layer 4 but, crucially, maintain a state table of active connections. This allows them to make more intelligent decisions, permitting return traffic for established connections without explicit rules. This significantly improves security and simplifies rule management.

- Proxy Firewalls (Application-Layer Gateways): Operating at the application layer (Layer 7), proxy firewalls act as intermediaries between internal and external systems. They terminate the connection from the internal client, inspect the application-layer traffic, and then establish a new connection to the external server. This provides deep inspection and can filter based on application-specific commands, but introduces latency.

- Next-Generation Firewalls (NGFWs): Representing a significant advancement, NGFWs integrate traditional firewall capabilities with additional security features. Key NGFW capabilities include:

- Application Awareness: Identify and control applications regardless of port or protocol, enabling granular control (e.g., allow Facebook but block Facebook games).

- Intrusion Prevention System (IPS): Detect and prevent known exploits, malware, and other threats by analyzing traffic for signatures and behavioral anomalies.

- Deep Packet Inspection (DPI): Examine the actual content of packets, not just headers, to identify and block malicious content.

- User Identity Awareness: Integrate with directory services (e.g., Active Directory) to apply policies based on individual users or groups, rather than just IP addresses.

- Web Application Firewalls (WAFs): Specifically designed to protect web applications from common web-based attacks (e.g., SQL injection, cross-site scripting, zero-day exploits) by monitoring and filtering HTTP/HTTPS traffic.

- Unified Threat Management (UTM) Devices: Consolidate multiple security functions (firewall, antivirus, IPS, content filtering, VPN) into a single appliance, simplifying management for smaller organizations, though potentially creating a single point of failure.

2.3.2 Firewall Operating Principles

The effectiveness of a firewall hinges on its rule set and underlying principles:

- Rule Sets (Policies): Firewalls use a prioritized list of rules (policies) to evaluate traffic. Each rule specifies criteria (source/destination, port, protocol, application, user) and an action (permit, deny, drop).

- Implicit Deny: A fundamental security principle, the last rule in every firewall policy is almost always an implicit deny, meaning any traffic not explicitly permitted by a preceding rule is automatically blocked.

- Zones: Firewalls often define security zones (e.g., internal LAN, DMZ, external/Internet). Traffic flow and security policies are then defined between these zones, making policy management more intuitive and secure.

2.3.3 Deployment Modes

Firewalls can be deployed in various modes:

- Routed Mode (Layer 3): The firewall acts as a router, with its interfaces participating in routing protocols and having IP addresses in different subnets. This is common for perimeter firewalls.

- Transparent Mode (Layer 2): The firewall acts like a Layer 2 bridge, forwarding frames without needing to change IP addresses. It’s often used to insert a firewall into an existing network without re-addressing or changing routing.

2.3.4 Configuration Elements

Configuring a firewall involves several critical steps:

- Interface Configuration: Assigning IP addresses, security zones, and enabling/disabling security features on each interface.

- Security Policies/Rules: Defining granular rules to permit or deny specific traffic flows based on source, destination, service, application, and user.

- Network Address Translation (NAT) Rules: Configuring NAT for internal hosts to access external resources or for external access to internal servers (DNAT).

- VPN Configurations: Setting up IPsec or SSL VPN tunnels for secure remote access or site-to-site connectivity.

- Logging and Monitoring: Configuring the firewall to log traffic, security events, and administrative actions, and integrating with SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) systems for centralized analysis.

Proper configuration of firewalls is arguably the most critical aspect of network security, forming an impenetrable barrier against unauthorized access, cyberattacks, and other pervasive security threats. Regular review and optimization of firewall rules are essential to adapt to evolving threat landscapes and organizational needs.

2.4 Other Critical Components

While routers, switches, and firewalls form the backbone, several other components play crucial roles and require careful configuration:

2.4.1 Load Balancers

Load balancers distribute incoming network traffic across multiple servers or resources to ensure high availability, optimal resource utilization, and improved application performance. They operate at Layer 4 (TCP/UDP) or Layer 7 (HTTP/HTTPS) and can perform health checks on backend servers to direct traffic only to healthy instances. Configuration involves defining virtual servers, backend server pools, load balancing algorithms (e.g., round-robin, least connections), and health monitors.

2.4.2 Wireless Access Points (WAPs)

WAPs enable wireless connectivity for devices, bridging wireless clients to the wired network. Their configuration is critical for security and user experience:

- SSID Management: Configuring Service Set Identifiers (SSIDs) for different networks (e.g., corporate, guest), including hidden SSIDs for added security.

- Security Protocols: Implementing robust encryption (WPA2/WPA3 Personal or Enterprise) and authentication mechanisms (e.g., 802.1X with RADIUS server integration).

- VLAN Tagging: Assigning SSIDs to specific VLANs to segment wireless traffic from wired traffic and enforce policies.

- Roaming: Configuring WAPs for seamless client roaming between access points in larger deployments.

- RF Optimization: Adjusting channel, power levels, and antenna settings to minimize interference and maximize coverage.

2.4.3 Domain Name System (DNS) Servers

DNS servers translate human-readable domain names (e.g., example.com) into machine-readable IP addresses. Proper configuration of internal and external DNS services is vital for reliable name resolution, internet access, and service discoverability. Misconfigured DNS can lead to service outages and security vulnerabilities (e.g., DNS spoofing).

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Network Topologies and Configuration Implications

The physical and logical arrangement of network devices, known as network topology, profoundly influences configuration complexity, redundancy, performance, and scalability. Understanding the implications of various topologies is crucial for effective network design and configuration.

3.1 Common Network Topologies

- Star Topology: All devices connect to a central hub or switch. This simplifies configuration and troubleshooting for individual devices but makes the central device a single point of failure. Configurations are largely independent for each spoke, focusing on port settings on the central switch.

- Bus Topology: Devices are connected to a single cable, or ‘bus’. Simple for small networks but difficult to troubleshoot and prone to collisions. Not common in modern wired LANs but conceptually relevant for some wireless or IoT setups. Configuration involves minimal device-specific settings beyond basic addressing.

- Ring Topology: Devices are connected in a closed loop, with each device connected to exactly two others. Offers inherent redundancy if one link fails (e.g., FDDI, Token Ring). Configuration typically involves specific protocols for token passing or ring management and failover.

- Mesh Topology: Every device is connected to every other device (full mesh) or some devices are connected to multiple others (partial mesh). Offers maximum redundancy and fault tolerance, but is expensive and complex to implement and configure due to the large number of connections. Routing protocols must be carefully configured to leverage multiple paths.

- Hybrid Topology: A combination of two or more basic topologies. Most large-scale enterprise networks are hybrid (e.g., star-bus, star-ring). This combines the advantages of different topologies but increases configuration complexity, requiring careful integration of protocols and policies across different segments.

3.2 High Availability and Redundancy Designs

Modern network configurations heavily emphasize high availability (HA) to minimize downtime. This often involves specific topological and protocol configurations:

- Redundant Links and Devices: Deploying multiple physical connections and redundant hardware (e.g., dual power supplies, clustered firewalls, stacked switches). Configuration involves ensuring these redundant paths are active and properly managed by protocols like STP to prevent loops.

- First-Hop Redundancy Protocols (FHRPs): For default gateway redundancy in a LAN, FHRPs like HSRP (Hot Standby Router Protocol), VRRP (Virtual Router Redundancy Protocol), and GLBP (Gateway Load Balancing Protocol) allow multiple routers to act as a single logical default gateway. This ensures clients always have an available gateway even if a physical router fails.

- Link Aggregation (LAG/EtherChannel): Bundling multiple physical links into a single logical link increases bandwidth and provides redundancy. Protocols like LACP (Link Aggregation Control Protocol) and PAgP (Port Aggregation Protocol) automate the negotiation and management of these bundled links.

- Clustering: Many firewalls and load balancers can be configured in active-passive or active-active clusters to provide failover capabilities. Configuration ensures that state information is synchronized between devices for seamless failover.

Network topology dictates how devices are physically and logically arranged, directly impacting the types of configurations needed, the complexity of routing and switching protocols, and the overall strategy for ensuring performance, security, and availability.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Best Practices for Network Configuration

Effective network configuration goes beyond simply making devices operational; it involves adhering to a set of best practices that enhance performance, bolster security, and simplify management. These practices are crucial for building a resilient and efficient digital infrastructure.

4.1 Performance Optimization

Optimizing network performance involves strategically configuring devices and protocols to ensure efficient data flow and resource utilization.

4.1.1 Network Segmentation

Dividing the network into smaller, logically isolated segments is a cornerstone of performance optimization and security. While VLANs are the most common method for Layer 2 segmentation, advanced techniques extend this principle:

- VLANs: As discussed, VLANs reduce broadcast domains, isolate traffic, and enhance security by logically separating departments, services (e.g., VoIP, guest Wi-Fi, server farms), or applications. This minimizes congestion within each segment. (microstartups.org)

- Micro-segmentation: Taking segmentation to a finer granularity, micro-segmentation isolates workloads and applications at a much deeper level (e.g., individual virtual machines or containers). This significantly reduces the ‘blast radius’ of a security breach by limiting lateral movement within the network.

- Virtual Routing and Forwarding (VRFs): VRFs allow multiple independent routing tables to coexist on a single router, providing complete isolation for traffic. This is particularly useful for multi-tenant environments or for segmenting different business units on a shared infrastructure.

4.1.2 Quality of Service (QoS)

Implementing QoS policies ensures that critical applications and services receive preferential treatment over less time-sensitive traffic, guaranteeing necessary bandwidth and low latency. This is vital for real-time applications such as VoIP, video conferencing, and mission-critical enterprise applications. (cbtnuggets.com)

- Classification and Marking: Traffic is first identified (classified) based on criteria like IP address, port number, application signature, or VLAN. It is then ‘marked’ using fields like Differentiated Services Code Point (DSCP) in the IP header or Class of Service (CoS) in the 802.1Q header. These marks inform downstream devices about the traffic’s priority.

- Queuing and Scheduling: Devices maintain multiple queues for different traffic classes. Scheduling algorithms (e.g., Weighted Fair Queuing, Class-Based Weighted Fair Queuing, Low Latency Queuing) determine how packets are taken from these queues and sent out, prioritizing higher-marked traffic.

- Shaping and Policing: Traffic shaping buffers excess traffic to smooth out bursts, while policing drops or re-marks excess traffic to enforce bandwidth limits. These mechanisms prevent congestion and ensure fairness.

4.1.3 Regular Monitoring and Baselining

Continuous monitoring of network performance is essential for identifying bottlenecks, latency issues, abnormal traffic patterns, and other performance-related problems proactively. (datacalculus.com) Tools such as SNMP (Simple Network Management Protocol), NetFlow/sFlow/IPFIX, and network performance monitors provide critical insights into device health, interface utilization, and application performance. Establishing performance baselines allows administrators to quickly detect deviations from normal behavior, indicating potential issues or attacks.

4.1.4 Redundancy and High Availability

Designing the network with redundancy at multiple layers prevents single points of failure. This includes:

- Device Redundancy: Deploying redundant power supplies, dual control planes, and clustering devices like firewalls and load balancers.

- Link Redundancy: Using multiple physical paths between devices, often combined with Link Aggregation (LACP/PAgP) and Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) for Layer 2 redundancy.

- Gateway Redundancy: Implementing First-Hop Redundancy Protocols (FHRPs) such as HSRP, VRRP, or GLBP to ensure default gateway availability for end devices.

4.2 Security Enhancement

Fortifying network security requires a multi-layered approach that permeates all configuration decisions.

4.2.1 Robust Access Control

Implementing strong authentication and authorization mechanisms is paramount to restrict access to network devices and resources. (calyptix.com)

- AAA (Authentication, Authorization, Accounting): Utilize centralized AAA servers (e.g., RADIUS, TACACS+) to manage access to network devices. This ensures consistent policies, simplifies user management, and provides audit trails.

- Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Assign permissions based on user roles (e.g., network admin, monitoring, guest) rather than individual users, simplifying management and enforcing the principle of least privilege.

- Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Mandate MFA for accessing critical network infrastructure components to significantly reduce the risk of credential compromise.

- Management Plane Hardening: Limit access to management interfaces (SSH, HTTPS) to specific trusted IP addresses or management VLANs. Disable insecure protocols like Telnet and HTTP.

4.2.2 Secure Device Hardening

Network devices, by default, often come with configurations that are not secure. Hardening involves tailoring these settings to minimize attack surface:

- Change Default Credentials: Immediately change all default usernames and passwords for every device.

- Disable Unnecessary Services: Turn off all unused ports, services, and features (e.g., HTTP, SNMP v1/v2c, Finger, CDP/LLDP if not required) to reduce potential attack vectors.

- Secure Protocols: Enforce the use of secure protocols like SSHv2 for remote management, HTTPS for web interfaces, and SNMPv3 for network monitoring.

- Control Plane Policing (CoPP): Configure routers and switches to protect their own CPU and memory from excessive traffic, particularly malicious traffic targeting the control plane (e.g., routing updates, management protocols).

4.2.3 Regular Updates and Patch Management

Keeping device firmware and software up to date is non-negotiable for addressing known vulnerabilities, patching security flaws, and enhancing security features. (calyptix.com)

- Vulnerability Management Program: Establish a systematic process for identifying, assessing, and remediating vulnerabilities. This includes subscribing to vendor security advisories and regularly scanning network devices.

- Staging and Testing: Implement a testing environment to validate updates and patches before deploying them to production, ensuring compatibility and stability.

4.2.4 Granular Firewall Configuration

Firewalls are the primary enforcement point for network security policies. Their configuration must be meticulous. (eccouncil.org)

- Principle of Least Privilege: Configure firewalls to restrict inbound and outbound traffic to only what is absolutely necessary for business operations. Adopt a ‘default deny’ posture, explicitly permitting only required services and destinations.

- Application-Layer Inspection: Leverage Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW) capabilities for application-aware policies, allowing control over specific applications regardless of the ports they use.

- Intrusion Detection/Prevention Systems (IDS/IPS): Integrate IDS/IPS capabilities to detect and block malicious traffic patterns, known exploits, and malware.

- Geo-blocking: Block traffic from countries or regions that have no legitimate reason to interact with the organization’s network.

- Continuous Rule Review: Regularly audit firewall rules to remove obsolete entries, optimize order, and ensure they align with current security policies and business needs.

4.2.5 Network Segmentation for Security

Beyond performance, segmentation is a critical security control:

- Demilitarized Zone (DMZ): Implement a DMZ for publicly accessible services (e.g., web servers, email servers) to isolate them from the internal LAN. This limits the impact if these public services are compromised.

- Zero-Trust Network Architecture (ZTNA): Evolve towards a zero-trust model where no user or device, whether inside or outside the network perimeter, is inherently trusted. Access is granted on a least-privilege, ‘need-to-know’ basis after continuous verification.

4.2.6 Logging and Auditing

Comprehensive logging and regular auditing are vital for security monitoring, incident response, and compliance:

- Centralized Logging: Configure all network devices to send their logs to a centralized Syslog server or a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system. This provides a single pane of glass for monitoring, correlation, and analysis of security events.

- Audit Trails: Ensure configuration changes, login attempts, and critical security events are logged, providing an immutable audit trail for forensic investigations and compliance reporting.

4.3 Documentation and Change Management

These practices are often overlooked but are fundamental to maintaining a healthy and secure network.

4.3.1 Comprehensive Documentation

Accurate and up-to-date documentation is the bedrock of effective network management. Without it, managing, troubleshooting, and auditing configurations become exceedingly challenging. (datacalculus.com)

- Network Diagrams: Maintain logical and physical network topology diagrams, including IP addressing schemes, VLAN assignments, and device interconnections.

- IP Address Management (IPAM): Implement an IPAM solution to track IP address allocation, subnet usage, and DNS records.

- Configuration Baselines and Templates: Store baseline configurations for all device types and use standardized templates for new deployments to ensure consistency.

- Service Descriptions: Document purpose, dependencies, and expected behavior for all network services and applications.

- Disaster Recovery Plans: Detail procedures for restoring network services in case of an outage or disaster.

4.3.2 Structured Change Management

A formal change management process is crucial to prevent unauthorized or untested changes from destabilizing the network. This process should include:

- Change Request: A formal submission detailing the proposed change, its scope, and justification.

- Impact Analysis: Assessing the potential effects of the change on other systems and services.

- Approval Workflow: Review and approval by relevant stakeholders (e.g., security, operations management).

- Implementation Plan: Detailed steps for execution, including a rollback plan in case of issues.

- Validation: Procedures to verify the change was successful and did not introduce new problems.

- Communication: Notifying affected users and teams about scheduled changes and potential impacts.

By diligently following these best practices, organizations can build and maintain a network infrastructure that is not only high-performing and secure but also manageable and adaptable to future challenges.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Common Pitfalls Leading to Misconfigurations

Despite the clear advantages of best practices, network misconfigurations remain a prevalent issue, often stemming from a range of identifiable pitfalls. These errors can severely compromise network security, degrade performance, and lead to operational disruptions. Understanding these common traps is the first step toward avoiding them.

5.1 Inadequate Documentation and Lack of Baselines

One of the most significant pitfalls is the absence of comprehensive and up-to-date documentation. (datacalculus.com)

- Impact: Without detailed network diagrams, IP addressing plans, and configuration files, it becomes incredibly challenging to troubleshoot issues, implement changes, or onboard new team members. Over time, administrators may make changes without a full understanding of the network’s current state, leading to unintended consequences and drift. Lack of a documented baseline configuration means there’s no reference point for identifying unauthorized or erroneous changes.

- Consequences: Prolonged troubleshooting times, increased risk of human error, difficulty in maintaining consistency, and non-compliance with regulatory requirements that demand auditable documentation.

5.2 Insufficient Training and Skill Gaps

Network administrators lacking adequate training or experience with specific technologies are prone to making configuration errors. (datacalculus.com)

- Impact: Complex features like OSPF area design, intricate BGP policy routing, or advanced firewall rule sets require specialized knowledge. Inexperienced staff might apply generic solutions that don’t fit the specific network context, or inadvertently create security holes by misconfiguring access controls or VPNs.

- Consequences: Security vulnerabilities, performance degradation, instability, and an inability to leverage the full capabilities of expensive network equipment.

5.3 Overlooking Security Policies and Compliance

Failing to adhere to established security policies, industry standards, or regulatory compliance mandates can lead to critical misconfigurations. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Impact: This includes leaving default passwords, enabling insecure services (e.g., Telnet, HTTP for management), not implementing strong access control lists, or neglecting to patch known vulnerabilities. Organizations may also overlook compliance with regulations like GDPR, HIPAA, or PCI DSS, resulting in configurations that expose sensitive data.

- Consequences: Data breaches, unauthorized access, ransomware attacks, regulatory fines, reputational damage, and loss of customer trust.

5.4 Lack of Version Control

Many organizations still manage network configurations as simple text files without any formal version control system.

- Impact: Without version control, tracking changes, identifying who made them, when they were made, and why, becomes nearly impossible. This makes reverting to a previous stable state extremely difficult and fosters inconsistencies across devices.

- Consequences: Configuration drift (discussed in the next section), extended downtime during incidents, and an inability to audit changes effectively.

5.5 Manual Configuration and Scale Challenges

Reliance on manual configuration for large or complex networks is a recipe for errors and inconsistencies.

- Impact: Typing commands manually, even with copy-pasting, is prone to typos, omissions, and variations across devices. As the network scales, the task becomes overwhelming, making it impossible to ensure uniform configuration across hundreds or thousands of devices.

- Consequences: Human error, inconsistent security policies, performance variations, slow deployment of new services, and increased operational costs.

5.6 Inadequate Testing

Deploying configuration changes directly to production without prior testing in a lab or staging environment is a high-risk practice.

- Impact: Changes, even seemingly minor ones, can have unforeseen ripple effects across the network, leading to outages or performance issues that disrupt critical business operations.

- Consequences: Network downtime, service interruptions, emergency rollbacks, and erosion of confidence in the network team.

5.7 Default Settings and Weak Credentials

Many devices ship with default usernames, passwords, or SNMP community strings that are publicly known. Similarly, leaving default configurations active can create vulnerabilities.

- Impact: Attackers routinely scan for devices using default credentials or open services. If discovered, they can easily gain unauthorized access, leading to full network compromise.

- Consequences: Complete loss of control over network devices, data theft, and system sabotage.

By actively recognizing and addressing these common pitfalls, organizations can significantly reduce the incidence of misconfigurations, thereby enhancing network stability, security, and operational efficiency.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Techniques for Configuration Drift Management

Configuration drift, defined as the unauthorized or unintended deviation of network configurations from their intended, documented, or baseline state, is a pervasive challenge in network management. It often results from ad-hoc manual changes, lack of oversight, or incomplete change management processes. Unmanaged drift can lead to security vulnerabilities, performance issues, compliance failures, and increased troubleshooting complexity. Effective configuration drift management requires a proactive and systematic approach, often leveraging automation and rigorous processes.

6.1 Automated Configuration Management Platforms

Leveraging specialized tools that automate the deployment, management, and verification of network configurations is the most effective strategy for combating drift. (datacalculus.com)

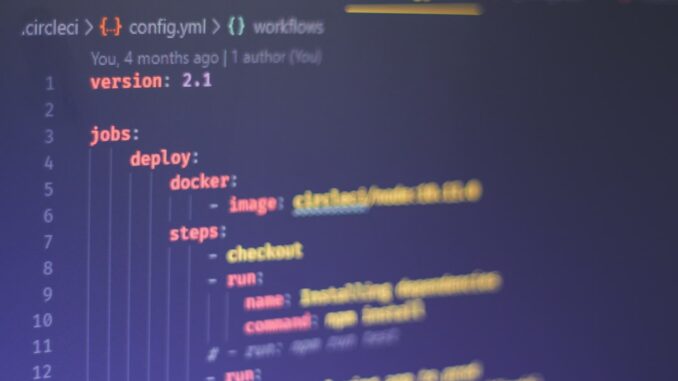

- Infrastructure as Code (IaC): This paradigm involves defining network configurations in human-readable, machine-executable code (e.g., YAML, JSON). Tools like Ansible, Puppet, Chef, and SaltStack use these code definitions to automatically configure devices, ensuring consistency. If a device’s configuration deviates from the code, the automation platform can detect it and either report it or automatically remediate it by reapplying the desired state.

- Desired State Configuration (DSC): Many automation tools operate on a DSC principle. Administrators define the ‘desired state’ of the network device (e.g., ‘port Fa0/1 must be in VLAN 10 and have port security enabled’). The automation engine then continuously monitors devices and enforces this desired state, correcting any drift automatically.

- Benefits: Reduces human error, ensures uniformity across devices, accelerates deployment of changes, and provides an auditable history of configuration activities.

6.2 Regular Audits and Compliance Checks

Periodic and systematic audits are crucial to compare current device configurations against established baseline configurations or compliance standards, identifying and rectifying deviations promptly. (datacalculus.com)

- Automated Audit Tools: Dedicated network audit and compliance tools can automatically collect configurations from all devices, compare them against predefined templates or security policies, and generate reports highlighting discrepancies. These tools can also check for compliance with industry standards (e.g., PCI DSS, HIPAA) or internal security policies.

- Baseline Comparison: A ‘golden configuration’ or baseline configuration should be established for each type of device. Audits then regularly compare the running configurations against this baseline. Any difference indicates potential drift.

- Benefits: Proactive identification of unauthorized changes, ensuring compliance with internal and external regulations, and providing necessary documentation for audits.

6.3 Version Control Systems (VCS) for Configurations

Implementing version control systems, commonly used in software development, to track changes in network configurations is a fundamental practice for managing drift. (datacalculus.com)

- Git for Network Configs: Tools like Git allow network teams to store configuration files in repositories, track every change, identify who made the change, when it was made, and include a commit message explaining the change. This provides an immutable history of all modifications.

- Branching and Merging: VCS enables branching for developing new features or testing changes in isolation before merging them into a stable main branch. This facilitates collaboration and reduces the risk of introducing errors into production.

- Rollback Capability: In case a deployed configuration causes issues, the VCS allows for quick and reliable rollback to a previous, stable version, minimizing downtime.

- Peer Review: Implementing a process where proposed configuration changes are reviewed by other team members (e.g., via pull requests in Git) before being merged enhances quality and catches potential errors.

6.4 Network Monitoring and Alerting

Integrating drift detection with real-time network monitoring and alerting systems provides immediate notification of unauthorized changes.

- Configuration Change Alerts: Monitoring systems can be configured to alert administrators whenever a configuration change is detected on a device, often by comparing the running configuration with the last saved version or a baseline.

- Integration with SIEM: Sending configuration change events to a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system allows for correlation with other security events, providing a more holistic view of potential threats or compliance issues.

By combining automated configuration management, regular audits, robust version control, and real-time monitoring, organizations can establish a comprehensive strategy to effectively manage configuration drift, ensuring network stability, security, and compliance.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

7. Role of Network Automation in Configuration Lifecycle Management

Network automation has emerged as a transformative force in the IT landscape, fundamentally reshaping how network configurations are managed throughout their entire lifecycle. Moving beyond manual, CLI-driven operations, automation brings efficiency, consistency, and scalability, addressing the growing complexity and demands of modern networks.

7.1 Paradigm Shift: From Manual to Programmatic

The traditional approach to network configuration involved network engineers manually connecting to devices (via CLI or GUI) and executing commands. This method is slow, prone to human error, and doesn’t scale. Network automation introduces a paradigm shift towards programmatic configuration, where networks are treated as code.

7.2 Configuration Lifecycle Stages and Automation’s Impact

Network automation plays a pivotal role in managing every stage of the configuration lifecycle:

7.2.1 Provisioning and Initial Deployment

- Zero-Touch Provisioning (ZTP): Automation enables ZTP, where new devices can be powered on, automatically discover a configuration server, download their initial configuration, and integrate into the network without manual intervention. This dramatically speeds up deployments and reduces errors.

- Templating and Standardization: Configuration templates (e.g., Jinja2 for Ansible) allow for standardized configurations across devices. Variables can be used to customize unique parameters (IP addresses, hostnames), ensuring consistency while adapting to specific needs.

7.2.2 Day-2 Operations and Maintenance

- Bulk Updates and Changes: Automation tools can push configuration changes to hundreds or thousands of devices simultaneously, ensuring consistency for policy enforcement, VLAN modifications, or QoS adjustments across the entire network. This is far more efficient than manual updates.

- Policy Enforcement: Automated systems can continuously monitor and enforce network policies (e.g., security ACLs, routing preferences), automatically detecting and remediating any deviations.

- Routine Maintenance: Tasks like backing up configurations, generating reports, or restarting services can be scheduled and executed automatically, freeing up engineers for more strategic work.

7.2.3 Monitoring and Auditing

- Automated Compliance Checks: Automation tools can regularly audit network configurations against internal security policies, industry best practices, or regulatory standards (e.g., PCI DSS, HIPAA). Deviations are flagged and can be automatically corrected.

- Performance Monitoring Setup: Automation can configure SNMP, NetFlow, or Syslog settings on new and existing devices, ensuring consistent monitoring data collection for network visibility.

7.2.4 Decommissioning

- Automated Removal: When devices or services are decommissioned, automation can ensure their configurations are properly removed from the network (e.g., deleting VLANs, routing entries, firewall rules), preventing residual configuration clutter and potential security risks.

7.3 Key Benefits of Network Automation

Network automation delivers a multitude of advantages across operational, financial, and security dimensions:

7.3.1 Enhanced Efficiency and Speed

Automating routine and repetitive configuration tasks drastically reduces manual intervention, leading to significantly faster deployment of new services, quicker execution of changes, and reduced operational overhead. This translates to greater agility in responding to business needs.

7.3.2 Improved Consistency and Accuracy

By eliminating human error inherent in manual configuration, automation ensures that configurations are applied uniformly across the entire network. This maintains consistency with organizational standards and policies, reducing the risk of misconfigurations that can lead to performance issues or security vulnerabilities.

7.3.3 Facilitating Scalability and Agility

As networks grow in size and complexity, automation simplifies the process of scaling configurations to accommodate new devices, services, and locations. Organizations can rapidly deploy new infrastructure without a proportional increase in manual effort, thereby enhancing agility and responsiveness.

7.3.4 Stronger Security Posture

Automation enforces security policies consistently, reduces the attack surface by disabling unnecessary services, and facilitates rapid patching of vulnerabilities. It also helps in detecting and remediating configuration drift that could introduce security gaps, thereby strengthening the overall security posture.

7.3.5 Cost Reduction

Reduced manual labor, fewer incidents caused by misconfigurations, faster troubleshooting, and optimized resource utilization all contribute to significant cost savings in network operations.

7.4 Tools and Technologies for Network Automation

The ecosystem of network automation tools is diverse and continually evolving:

- Scripting Languages: Python is a dominant language in network automation due to its extensive libraries (e.g., Netmiko, Paramiko, NAPALM) for interacting with network devices via SSH, Telnet, or APIs. PowerShell is also used for Windows environments.

- Configuration Management Tools: Platforms like Ansible, Puppet, Chef, and SaltStack are widely adopted. Ansible, being agentless, is particularly popular for its simplicity and YAML-based playbooks for defining desired states and tasks.

- Network Orchestration Platforms: Vendor-specific (e.g., Cisco DNA Center, Juniper Apstra, Arista CloudVision) and open-source (e.g., OpenStack Neutron) orchestration platforms provide higher-level automation, abstracting device-specific configurations and managing entire network domains based on business intent.

- APIs (Application Programming Interfaces): Modern network devices expose RESTful APIs, allowing programmatic interaction and integration with automation tools. This moves away from screen scraping or CLI parsing to structured data exchange.

- SD-WAN and SDN: Software-Defined Wide Area Networking (SD-WAN) and Software-Defined Networking (SDN) principles inherently rely on automation and centralized control. They allow for network configuration and policy enforcement from a central controller, abstracting the underlying hardware.

Network automation is no longer a luxury but a strategic imperative. It enables organizations to build more resilient, agile, and secure networks, transforming network configuration from a laborious task into a streamlined, policy-driven process that supports business innovation and growth.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

8. Future Trends in Network Configuration

The landscape of network configuration is in a state of continuous evolution, driven by advancements in artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and the increasing demand for agile, resilient, and highly secure digital infrastructures. Several key trends are poised to redefine how networks are designed, deployed, and managed.

8.1 Intent-Based Networking (IBN)

Intent-Based Networking represents a profound shift from traditional, command-line-driven configuration to a more abstract, business-centric approach. With IBN, network administrators define high-level business ‘intent’ (e.g., ‘ensure all VoIP traffic has priority,’ ‘segment patient data from guest Wi-Fi,’ ‘provide secure access for remote employees’). The IBN system, using advanced analytics, machine learning, and automation, then translates this intent into device-specific configurations, deploys them, and continuously monitors the network to ensure the intent is met. If the network deviates, the system automatically remediates to restore the desired intent. This reduces manual effort, prevents misconfigurations, and ensures alignment with business objectives.

8.2 Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML) in Network Operations (AIOps)

AI and ML are increasingly being integrated into network configuration and operations (AIOps) to enhance capabilities that are beyond human capacity.

- Predictive Analytics: AI/ML algorithms can analyze vast amounts of network telemetry data (logs, performance metrics, traffic patterns) to predict potential failures or performance bottlenecks before they occur, allowing for proactive configuration adjustments.

- Anomaly Detection: ML models can learn ‘normal’ network behavior and instantly flag deviations that might indicate a security breach, misconfiguration, or performance issue, reducing mean time to detection (MTTD).

- Self-Healing Networks: In more advanced stages, AI-driven systems could automatically generate and deploy corrective configurations in response to detected issues, moving towards self-optimizing and self-healing networks.

- Configuration Optimization: AI can analyze network performance under various load conditions and suggest optimal configurations for routing, QoS, or firewall policies to maximize efficiency.

8.3 Edge Computing and IoT Configuration Challenges

The proliferation of Edge Computing and the Internet of Things (IoT) introduces new complexities and configuration demands.

- Distributed Configuration: Edge devices and IoT sensors often operate in highly distributed, geographically dispersed, and resource-constrained environments. Managing and securing configurations for thousands or millions of such devices manually is impossible.

- Automated Provisioning and Security: Automation and template-driven configurations become critical for deploying, updating, and securing these edge devices at scale. Zero-touch provisioning and robust security configurations for resource-limited devices are paramount.

- Low-Power Network Protocols: Configuration must account for specialized low-power wide-area network (LPWAN) technologies and protocols.

8.4 Cloud-Native Networking and Hybrid Cloud Integration

The adoption of cloud-native applications and hybrid cloud architectures requires seamless integration and consistent configuration between on-premises networks and public/private cloud environments.

- Network as a Service (NaaS): Consumption of networking capabilities as a service from cloud providers, with configuration managed through cloud APIs and orchestration.

- Unified Policy Enforcement: Ensuring consistent security policies, access controls, and network segmentation across diverse environments (on-prem, IaaS, PaaS, SaaS) through abstracted configuration layers and potentially federated identity management.

- Infrastructure as Code (IaC) for Cloud: Using tools like Terraform or CloudFormation to define and manage network configurations in cloud environments, ensuring consistent deployments and preventing drift.

8.5 Cybersecurity Mesh Architecture

The traditional perimeter-based security model is inadequate for modern, distributed networks. Cybersecurity Mesh Architecture (CSMA) is an evolving concept that advocates for a distributed approach to security controls, where individual components have their own perimeter.

- Micro-Perimeters: Network configuration will increasingly involve defining and enforcing granular security policies around every access point, endpoint, and workload, rather than relying solely on a monolithic firewall.

- Context-Aware Security: Configurations will become more dynamic, adapting security policies based on context (user identity, device posture, location, time) rather than static IP addresses.

- API-Driven Security: Security configurations will be heavily driven by APIs, enabling automated policy orchestration and integration across diverse security tools and network devices.

These trends highlight a future where network configuration is less about manual command entry and more about defining desired outcomes, leveraging intelligent systems for automated deployment, continuous verification, and proactive adaptation. Network professionals will shift from being command-line operators to architects and strategists of highly automated, resilient, and intelligent networks.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

9. Conclusion

This comprehensive exploration underscores the critical and evolving role of network configuration as the bedrock of modern digital infrastructure. From the foundational components like routers, switches, and firewalls to advanced concepts in automation and future trends, a meticulous approach to configuration is indispensable for any organization aiming to achieve operational excellence, robust security, and sustained competitive advantage. The intricate interplay of device-specific settings, protocol implementations, and architectural choices directly dictates a network’s performance, resilience, and susceptibility to threats.

The research has highlighted that adhering to established best practices, such as granular network segmentation, the strategic implementation of Quality of Service, robust access controls, and rigorous device hardening, is not merely advantageous but absolutely essential. These practices collectively form a multi-layered defense and optimization strategy that mitigates common pitfalls like inadequate documentation, skill gaps, and overlooked security policies, which frequently lead to debilitating misconfigurations.

Furthermore, the report emphasized the burgeoning significance of configuration drift management, detailing techniques such as automated configuration management platforms, regular compliance audits, and the indispensable role of version control systems. These methods are crucial for maintaining network integrity, ensuring continuous compliance, and enabling rapid recovery from unintended changes. Crucially, the transformative power of network automation has been thoroughly examined, demonstrating its pivotal role in enhancing efficiency, ensuring consistency, facilitating scalability, bolstering security, and ultimately reducing operational costs across the entire configuration lifecycle.

Looking ahead, the emergence of Intent-Based Networking, the integration of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning into network operations, and the evolving demands of Edge Computing, IoT, and hybrid cloud environments signal a future where network configuration will become even more dynamic, intelligent, and abstracted from low-level command entry. Network professionals must therefore evolve their skill sets, embracing programmatic approaches and automation tools to navigate this increasingly complex landscape.

In summation, a profound and comprehensive understanding of network configuration components, coupled with unwavering adherence to best practices, proactive drift management, and the strategic embrace of automation, is no longer an optional endeavor but a strategic imperative. By committing to these principles, organizations can not only mitigate the inherent risks associated with misconfigurations but also build a secure, high-performing, and agile network infrastructure that is resilient, adaptable, and capable of supporting the sustained innovation and growth demanded by the digital future.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

The section on security enhancement through robust access control is particularly insightful. How do you see the increasing adoption of zero-trust network access influencing the design and implementation of these controls in more complex, hybrid environments?

Thanks for highlighting the access control section! With zero-trust, we’re seeing a shift from traditional perimeter-based security to micro-segmentation. This requires more granular access policies, continuously verified identities, and adaptive controls tailored for each application and workload, especially across diverse environments.

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

Wow, quite the deep dive! But with all this talk of automation, are we just handing over the keys to the kingdom to Skynet? What happens when the AI decides *its* optimized configuration is best, even if it locks us all out?

That’s a great point! It’s definitely a balance. While automation offers huge efficiency gains, we need robust safeguards and human oversight. Defining clear boundaries and ethical guidelines for AI in network management is key to prevent unintended consequences. Perhaps ongoing risk assessment is required! What measures do you think are most critical?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

So, if misconfigurations are data breaches waiting to happen, are we *really* sure that comprehensive documentation is enough, or should we be teaching the routers to write their own memoirs? Think of the drama!

That’s a fun way to put it! Documentation is a start, but automating the validation and enforcement of configurations is really where the magic happens. Imagine AI generating those memoirs *and* flagging inconsistencies in real-time – now *that’s* a story worth reading! What other ways can we ensure continuous compliance?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

The point about AIOps enabling self-healing networks is fascinating. Considering the increasing complexity and scale, how can we effectively validate the AI’s configuration changes before they’re implemented to prevent unintended network-wide disruptions?

That’s a crucial question! Validating AI-driven changes is key. One approach is using simulated environments to model the network and test changes before deployment. This helps identify potential issues and allows for fine-tuning the AI’s configuration. What are your thoughts on using digital twins for this purpose?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

So, if network configuration is now code, does that mean we’ll be seeing more debugging and fewer late-night router reboots… or just entirely new, code-related ways for the network to spontaneously combust?

That’s a great question! While debugging is definitely part of the process, we’re hoping that Infrastructure as Code leads to *fewer* late-night emergencies. Centralized code management and robust testing can help catch potential issues early, avoiding those dreaded reboots. Do you think that continuous integration and deployment will help network stability?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

Regarding Intent-Based Networking, what level of abstraction is truly achievable, considering the persistent need to translate intent into specific device configurations across diverse vendor platforms?

That’s a great question! The ideal level of abstraction for Intent-Based Networking is one where network operators can express their intent in human-readable language, without needing detailed knowledge of specific device configurations. Translation is definitely complex, but standard data models, open APIs and vendor collaboration can assist in achieving greater abstraction. How do you feel about the trade-offs here?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

The discussion on structured change management is key. How can we ensure that impact analysis truly captures the complexities of interconnected systems, especially when changes might seem isolated?

That’s a great point. The interdependencies can be tricky to nail down. Perhaps incorporating automated dependency mapping tools, alongside manual reviews from cross-functional teams, could improve the accuracy of impact analysis. This could provide a more holistic understanding of potential consequences. What are your thoughts?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

Given the move toward intent-based networking, how do we reconcile the high-level business intent with the necessity for granular control in specialized environments, such as those with stringent regulatory requirements or unique performance needs?

That’s a very important consideration! In heavily regulated environments or where performance is paramount, the abstraction of intent-based networking can conflict with the need for fine-grained, manual adjustments. Perhaps policy-based translation layers offer a way to bridge this gap, allowing granular overrides where absolutely necessary. What are your experiences in highly-specialized industries?

Editor: StorageTech.News

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe